These bright spring weeks are the best time of year to be a lapsed Catholic. To this day, few things bring me greater pleasure than those sneaky bites of meat on Lenten Fridays.

Yet, even one as naughty as yours truly knows that old habits die hard. As I walked the pious streets of Rome last month, for example, I could not help but admire two millennia of tradition I’d hitherto mocked.

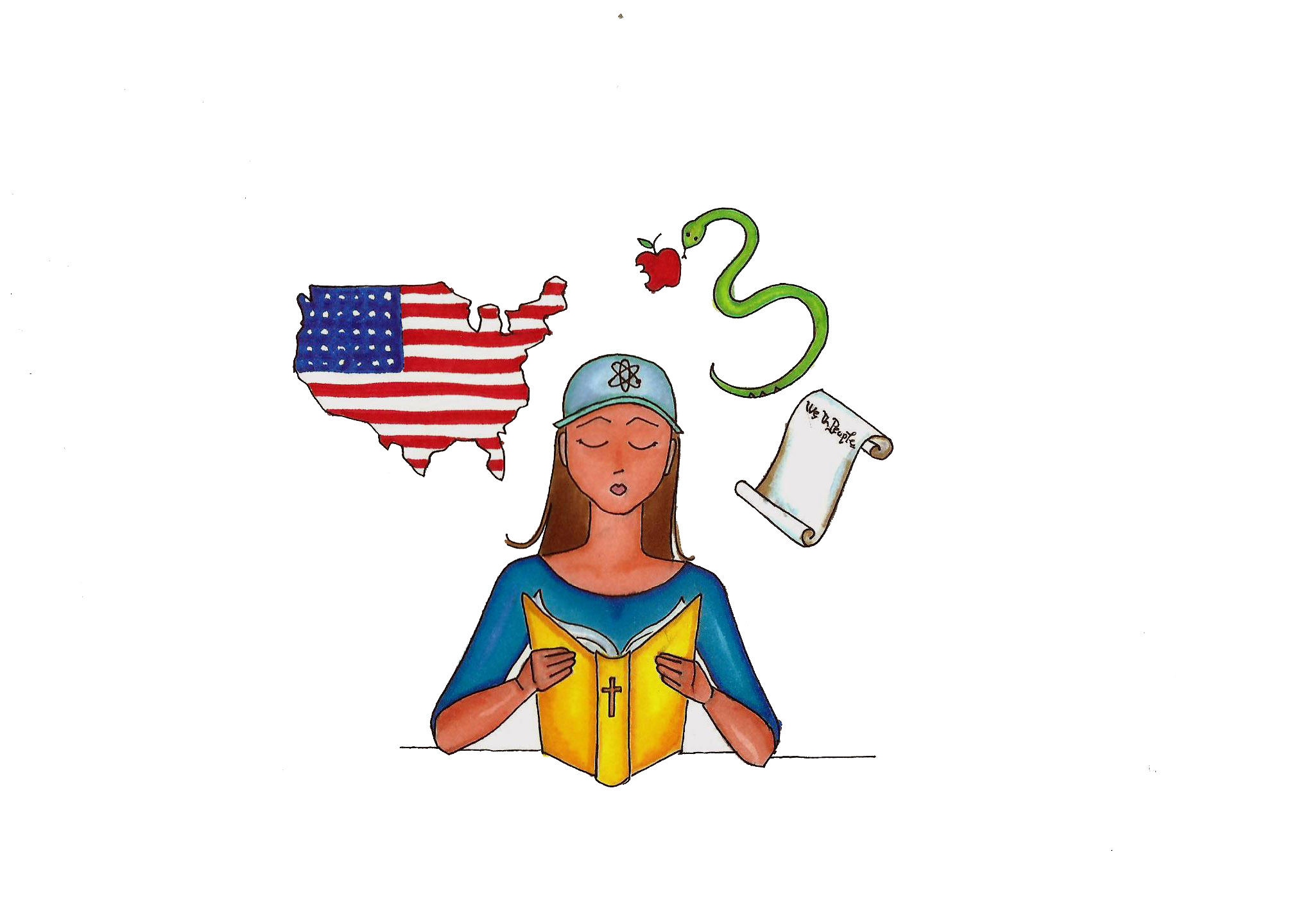

And in the spirit of self-abasement Lent calls us to assume, I shall make the biggest concession to Christianity I have ever dared: namely, that the Bible remains the single most important book in our culture that should be read by all, even and especially now.

This rings true for at least my more devout counterparts, who still implore me on my daily trek down Bruin Walk to join their Bible studies; afraid I might cripple the curve, I always politely decline.

But when I asked Robert Maniquis, a professor of English who teaches a course on biblical literature, about our generation’s overall biblical literacy, he offered one word straightaway: “bad.”

Some journalistic nudging broadened the vocabulary: “very slight.”

Such an appraisal is, of course, not a point of pride. No self-respecting heretic or atheist lacks a Bible on the bookshelf.

Nestled only half-mockingly between Charles Darwin and Ayn Rand sits a lovely copy of the good old King James Bible on mine. That version, whose 400th birthday is this May, has crept into millions of hotel rooms the world over. Its predecessor in English, the Geneva Bible, went on to shape the words and works of a man named William Shakespeare.

It is difficult to conceive of our language bereft of the idioms, maxims and metaphors derived from the Good Book. Its linguistic contribution alone should cement it as a keystone of our culture.

But more than that, the vagaries of history make little sense without whatever verse or doctrines men used to justify their deeds. To understand the Western world without knowing the Bible, Maniquis said, is like understanding one’s life without the years between age 15 and 30.

But why should I, no friend of orthodoxy, bother with the holy book of an ancient tribe and cult? For one, it is a matter of integrity.

It is the duty of the honest backslider to know what he abandons just as believers, I have warned before, ought to know what they profess.

More importantly, it is a matter of good taste. To know the Bible intimately is to share in the wellspring of values, rules, ideas and idioms that we, for better or for worse, are heir to. It is hardly a victory for secularism for our generation to neglect what came before us.

It is, contrarily, a deathblow to culture. When the mere word “Friday” evokes a very concrete image and a song to go along with it, while Moses et al are kept on the back burner, I must question whether we possess an identity worth having at all. The word “Philistine,” which once meant the biblical arch-nemeses of God’s chosen people, not incidentally refers now to the uncouth and lowbrow.

How the modern university ““ which began as a place to train priests ““ became a hotbed of cultural philistinism is a question for others to ponder. And whether administrators decide to instate more rigorous learning in the Holy Writ is a question to launch a thousand columns. As a rule, I treat with suspicion any and all who cling to the letter of old, obsolete documents; on the other hand, those who remain unversed in the Book fare no better.

If we are to salvage any semblance of our culture, the burden is upon us ““ for sophistication and excellence must be chosen personally, not coerced. To resurrect our culture, it pains me to say, will take more than bread alone.