Mollusk fossils shed light on the type of climate in the Pliocene epoch.

History repeats itself, even if it takes 4 million years.

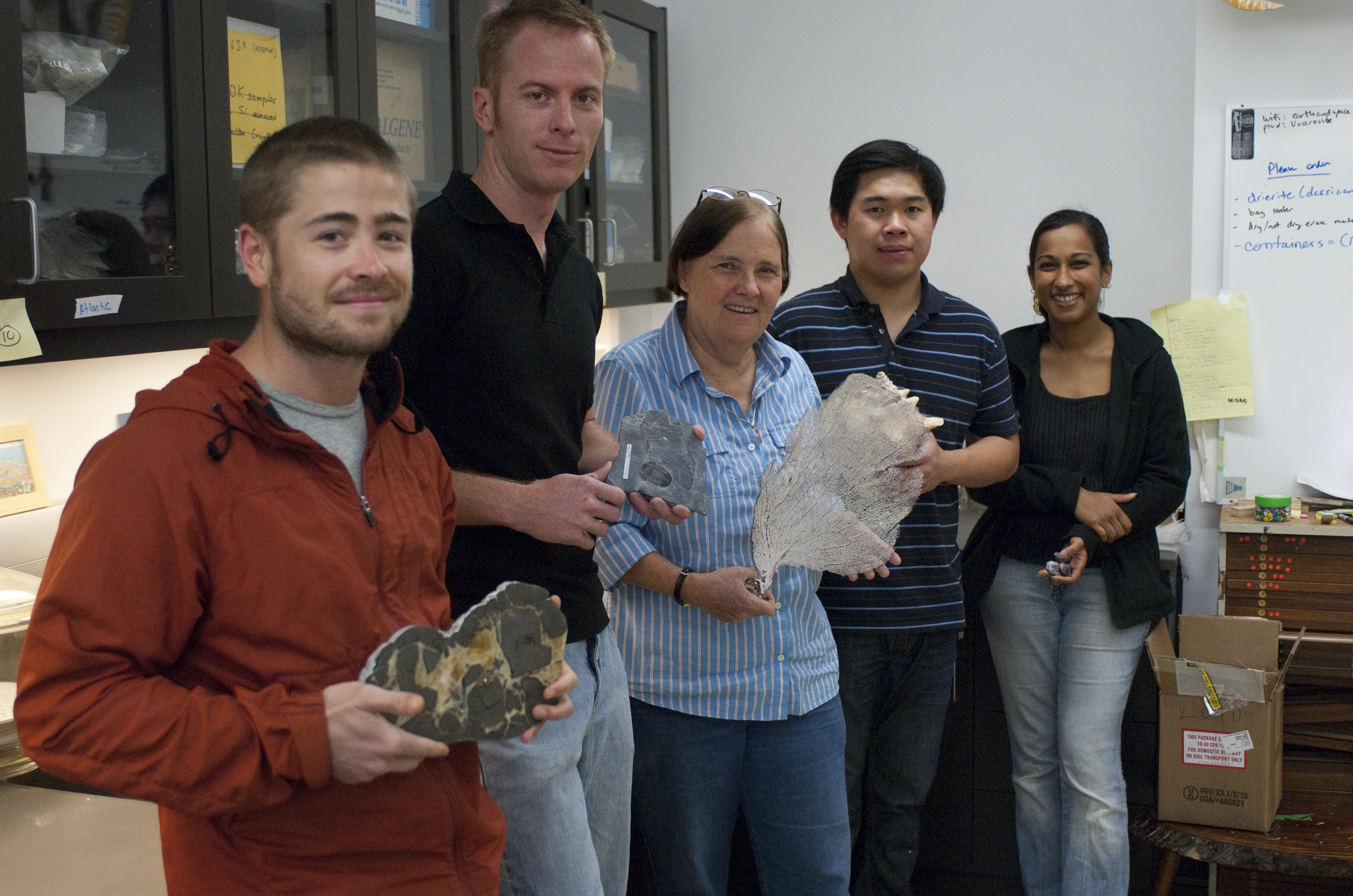

In a collaborative research project, Aradhna Tripati, assistant professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, has discovered a way to examine the conditions of arctic ice sheets between 3.5 and 4 million years ago ““ by using fossils.

A report of the research will appear in the April 15 issue of the geoscience journal, Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

In her research, Tripati and her colleagues analyzed fossils of mollusks at Beaver Pond, located in the far north region of Canada. Tripati said the data she and her colleagues collected may be able to paint a rough picture of the region’s future in the next 100 years.

“In the last century, the polar regions have experienced the most warming, and it’s the hardest to reproduce accurately in climate models,” Tripati said. “In the next 100 years, the arctic is predicted to warm more than other places.”

The Pliocene epoch occurred right before the most recent ice age, about 3.5 to 4 million years ago.

During that time, mollusks lived in the arctic region when summer ice caps melted completely, a situation that can be likened to the probable future of the zone, said Adam Csank, a doctoral student at the University of Arizona who coauthored the report with Tripati.

Csank first began research in 2004. He examined fossil wood to calculate approximate temperatures of the arctic region during the Pliocene epoch.

Later, he collaborated with Tripati and other researchers to collect information about the arctic during that time.

Though the researchers used five different means of data collection, they all generated the same conclusion that the arctic region of the future will begin to resemble its Pliocene state in coming years, said William Patterson, professor of geological sciences at the University of Saskatchewan and one of the researchers of the study.

Rather than looking at ice cores, which geologists have traditionally done to determine past climates, Tripati and her colleagues have been able to reach farther into time by examining mollusk fossils.

Tripati has been able to pinpoint the Pliocene as the last time carbon dioxide levels stabilized at 400 ppm, which she said has been unprecedented in the past 800,000 years.

“Our current climate has been unusual for the past 800,000 years,” Tripati said. “The current carbon dioxide levels have been unprecedented. We have to go pretty far back in geological time, before our modern species was around, to get a picture of what global climate looked like when carbon dioxide levels were (the same as they are) today.”

Recent research, including reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has predicted arctic temperatures to rise rapidly, by 10 degrees Celsius by 2100, reverting to the conditions of 4 million years ago.

As the group continues to collect information, they hope to generate a picture of the future arctic world, from atmospheric conditions to vegetation and wildlife, Csank said.

“It’s not a prediction of what will happen, but we can say something about cause and effect and what kinds of processes are important to consider in terms of natural history,” Tripati said.

As a result, Csank said their findings will help people prepare for the future.

“The scary thing is the rate of change is so much higher than in the past,” he said. “If you’re going to, in 100 years, do what happened in 5 million years, is it going to be too much change for ecosystems to adapt? It is possible that it will be.”