Despite Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak disabling the Internet in his country, UCLA students and Americans alike can remain connected with the riots in Egypt through tweets from John Scott-Railton.

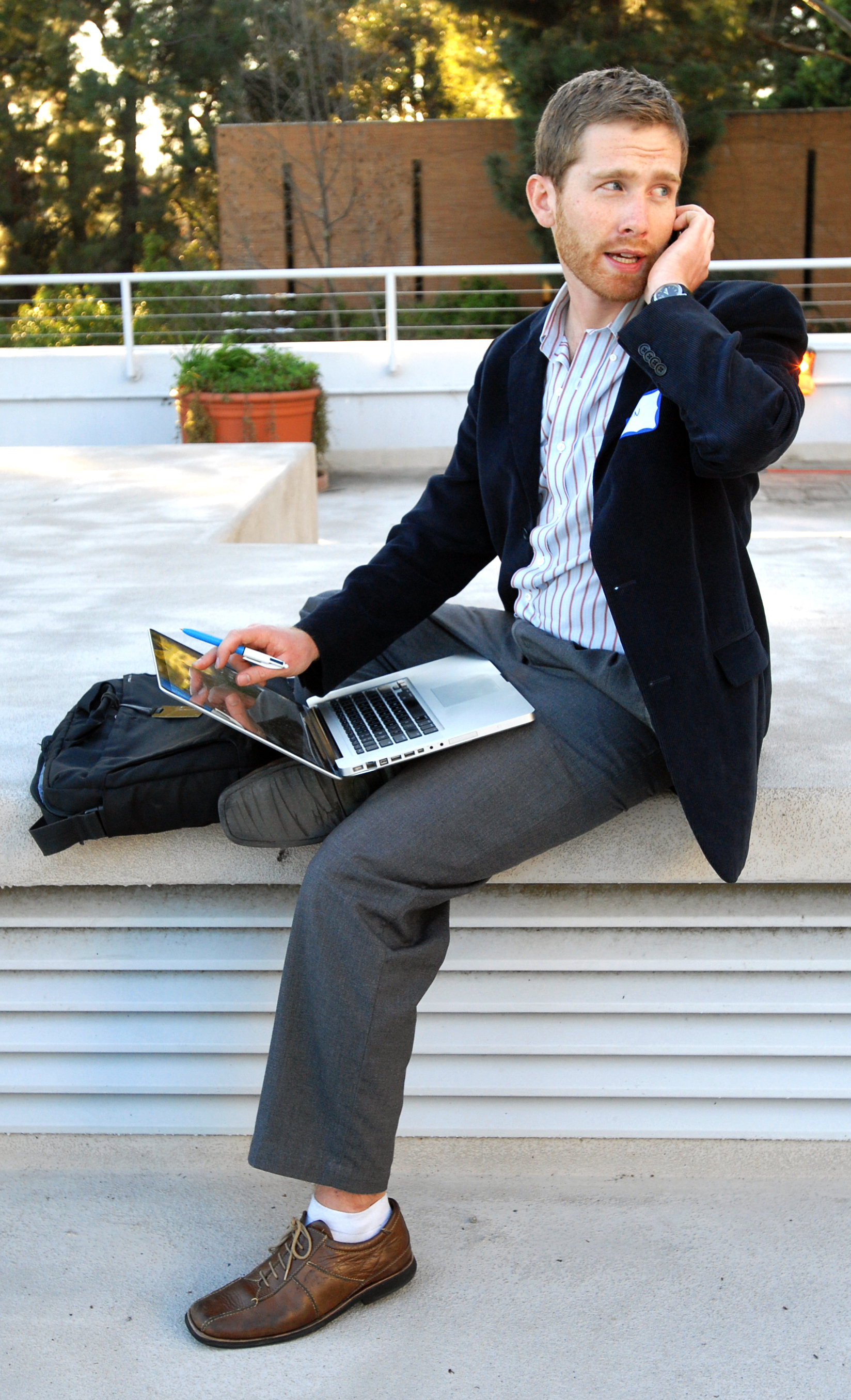

Scott-Railton, a doctorate student in urban planning, opened his first Twitter account on a computer in the UCLA School of Public Policy and Social Research, three days after the Jan. 25 riots occurred in Egypt.

Under the handle @Jan25voices, he represents the voice of a nation in revolt.

Not expecting to be the unofficial voice of Egypt, Scott-Railton had passed through Egypt in 2006, making friends whom he was able to contact before the Internet and mobile phones were disconnected by the Egyptian government. He received phone numbers for several of their landlines, which he now uses to channel updates on the situation in Egypt through Twitter.

In the Department of Urban Planning, students are taught to make the most out of the resources offered.

“I thought, maybe there’s something I could do,” Scott-Railton said.

@Jan25voices hosts more than 500 tweets and nearly 7,000 followers, including BBC and NPR.

Since the riots began, Scott-Railton has been able to provide vivid descriptions and sound clips from correspondents in Egypt to the rest of the world. His tweets vary from Egyptian patriot proclamations to detailed narrations of violence and conflict within the protests.

As evidenced by Scott-Railton’s efforts, the disconnection of the Internet has failed to prevent Egyptians from publicizing the events both inside and outside their country.

Egyptians have resorted to conventional forms of social networking, such as political flyers that connect Egyptians with authority figures and political leaders of the revolts,” said Steve Peterson, a professor of communication studies who teaches a class on social networking.

Peterson referred to the Facebook page, “We are all Khaled Said,” which he said played an integral role in organizing protests and mobilizing flyers prior to the disconnection of the Internet.

This is not the first time Facebook or Twitter have served as channels to political situations.

“In 2009, social networking was the forefront in political issues in Moldova and Iran,” Peterson said.

Nouri Gana, professor of comparative literature and Near Eastern languages and cultures, said more important than the social networking is the actual people behind the revolts.

Gana, a native of Tunisia, has remained connected with the revolution in his country through Skype and Facebook.

“(Social networks) cannot replace the people who carried out the revolutions,” Gana said in regards to both Egypt and Tunisia.

While these revolts come as a surprise to many, the actions of the Egyptians have been a function of the right mixture of circumstances, Scott-Railton said.

“It is not a single-person effort,” he said in regards to the many Egyptian Americans, ex-patriots of Egypt and members of the School of Public Policy who have helped him.

The goals of overthrowing their current governments, however, are not quite reached.

“There is still a lot to be done and a lot to achieve,” Gana said. “People across the Arab world have realized that what used to be impossible has now become a possibility.”

The efforts of Egyptians serve as a reminder of what a population is capable of, Scott-Railton said.

He said his role is small compared to the actions of the Egyptians, though.

“It’s what they’re doing, not what I’m doing,” Scott-Railton said. “It’s about how wrong people are to lose hope in a dictatorship that seems like it will never end. It’s a story about Arabs, Egyptians and North Africans making history together.”

Now, as he looks to continue contributing to the Egyptian revolution, Scott-Railton has the opportunity to be the narrator, or tweeter, of that story.