A study published in a research journal often becomes accepted ideology in the scientific community, influencing decisions made by medical professionals, researchers and the general public.

Yet the pressure to publish positive results in journals sometimes leads to the publication of misleading or inaccurate studies ““ the same studies used to determine which drugs doctors prescribe to patients, or whether or not to administer vaccines to children.

In 1997, a research group from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences published a study that positively linked breast cancer to dioxins, a group of environmental pollutants.

Lenore Arab, now a UCLA professor of nutritional epidemiology, was part of a team at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that set out to confirm the result using fat tissue.

What they found was that the link claimed by the NIEHS was false.

In fact, Arab’s data showed that dioxin exposure actually offered a bit of protection against breast cancer by blocking a certain receptor.

The team submitted the results to journals, but the researchers had a hard time finding a publisher because the NIEHS study had already staked the ground, Arab said.

“Basically our findings directly contradicted what was out there and what people wanted to hear,” Arab said.

The study finally appeared in the journal Pure Applied Chemistry in 2003 and has since become the confirmed result, she said.

Problems like the one Arab faced are not rare in research, however.

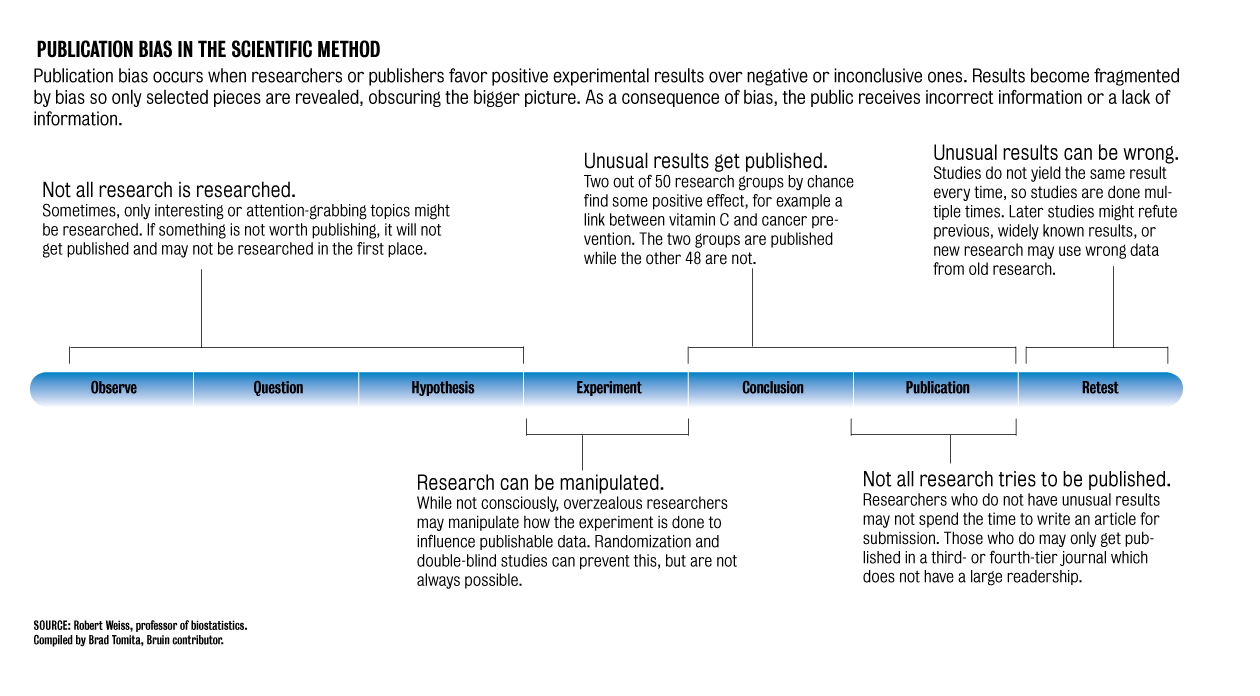

Publication bias ““ the trend to publish positive results rather than negative or inconclusive results ““ has always been a problem in research, said Robert Elashoff, a UCLA professor of biomathematics who teaches a course on controversies in clinical trials.

Recently, publication bias has garnered more attention in the press, as reports have surfaced of positive studies that are published and later found to be false, as in the case of the NIEHS study.

Because publication bias often occurs in journals, researchers who conduct a study that produces a negative or inconclusive result rarely publish, as negative studies are viewed as taking up space in journals, Arab said.

Although some researchers consider publication bias to be a problem, UCLA professor of neurology David Teplow said he believes this is up to interpretation.

Many journals do not consider all negative results to be significant enough to publish because some will do little to advance a field of research, Teplow said.

Whether a specific result is worthy of publication, though, is an issue to be decided by a publisher on a case-by-case basis.

By not publishing a negative study, however, other researchers may conduct the same study, not knowing that it has already been done, said Robert Weiss, UCLA professor of biostatistics.

Performing the same study multiple times may randomly result in a positive outcome, simply because of natural statistical variation. The truth of the study, however, will remain negative, Weiss said.

“Pick your favorite disease. If you have a treatment, and you don’t find anything, you put it away,” he said.

“If you try enough times, one of these times the study just happenstance will come out in favor of the treatment. The ones who found (the positive result) will be able to publish the paper.”

Because the underlying truth was that the study did not work, the next study will find a negative result, Weiss said.

“Now we have wasted a lot of money and time because nobody published the original result,” he said.

“In the meantime, we may be using a treatment that doesn’t work well. That is (an example of) publication bias really hurting us.”

Despite these dangers, publication bias persists. For UCLA biostatistics Professor Ron Brookmeyer, the issue boils down to incentives.

Journals want to be read and respected; researchers want to receive funding and be published.

Studies are frequently funded by pharmaceutical and drug companies, which hope to find a positive effect of their drugs, he said.

Researchers will also often use different statistical tests to get the best results for their study, Weiss said.

“Researchers have a very natural inclination to put the best face on something,” he said.

“It is not that they are overtly trying to do a bad job, but they may be optimistic about their (study), so they try four or five statistical ways.”

Though publication bias is not a new phenomenon, novel solutions to correct it are being developed.

Databases, which require researchers to register clinical trials performed and publish study designs ahead of time, are one step in the right direction, said Peter Butler, professor and chief of endocrinology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

“Science is a little slow to reject and uncover false positives. That may become less of a problem in the future now because of web-based information, which makes publishing easier,” said Michael Fanselow, a UCLA psychology professor. “But it remains to be seen.”

Butler added that the industry needs investigators, such as the National Institutes of Health, to monitor research in an unbiased manner ““ something that companies which stand to benefit from research results will not do.

While the severity of the problem is up to debate, Weiss said researchers do not intentionally try to publish false conclusions in studies.

“Scientists are not trying to do a bad job. We are trying very hard our entire lives to be very accurate about why … and how something works,” Weiss said.

“If we had a perfect solution, it would have been implemented.”