The 1994 Northridge earthquake caused billions of dollars in damage, more than 70 deaths and thousands of injuries.

The probability of a similar 6.7 magnitude quake happening again in the next 30 years? 99.7 percent.

Based on this data from the 2008 U.S. Geological Society earthquake forecast, it is clear scientists have determined that a huge quake should occur, though the exact date and location are difficult to determine.

The problem starts with the irregularity of earthquakes, said Paul Davis, professor of earth and space sciences.

But he added that scientists have found ways to get a more general idea of when the next tremor will happen, a process called forecasting.

This term refers to the possibility that an earthquake of a given size will occur in a specific place, said David Jackson, professor of geophysics.

Forecasting relies on a variety of factors, including the history of earthquakes in an area, the rate at which faults move in geologic time and the amount of strain on a fault.

The topic is currently being researched at UCLA, as professors are looking at the physics of earthquakes to better understand them.

With more understanding comes the possibility of more specific prediction, Davis said.

To do this, researchers look at statistics of past quakes around the globe.

But even this information is inconclusive.

“In any given place, we haven’t seen multiple earthquakes, so we don’t have enough data to get (pat-terns before quakes),” Davis said.

But while people disagree on these precursors, he said that the increase in understanding can make up for the lack of statistics.

Another process to determine the potential time and location of an earthquake is carbon dating, a process that involves the excavation of geological layers of earth.

With this technique, scientists can compile a record of when breaks in a fault occurred, sometimes going back 2,000 years.

This is especially pertinent to earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault, because research has shown that a quake originates there about every 150 years, Davis said.

Since the fault is the joint between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, an earthquake there causes about 10 meters of movement on either side of the break, Davis said.

The last major quake from the San Andreas Fault occurred in 1857, extending from the Carrizo Plain in San Luis Obispo County, through Fort Tejon in the Grapevine Canyon, to the Cajon Pass. Based on the data, Davis said it could be about time for another large earthquake to occur.

UCLA is located about 50 kilometers from the fault. The closest part of the San Andreas is outside of the San Gabriel mountains, between the cities of Palmdale and Wrightwood.

However, Davis said there were many “unknowns” as to how UCLA would fare in a major earthquake.

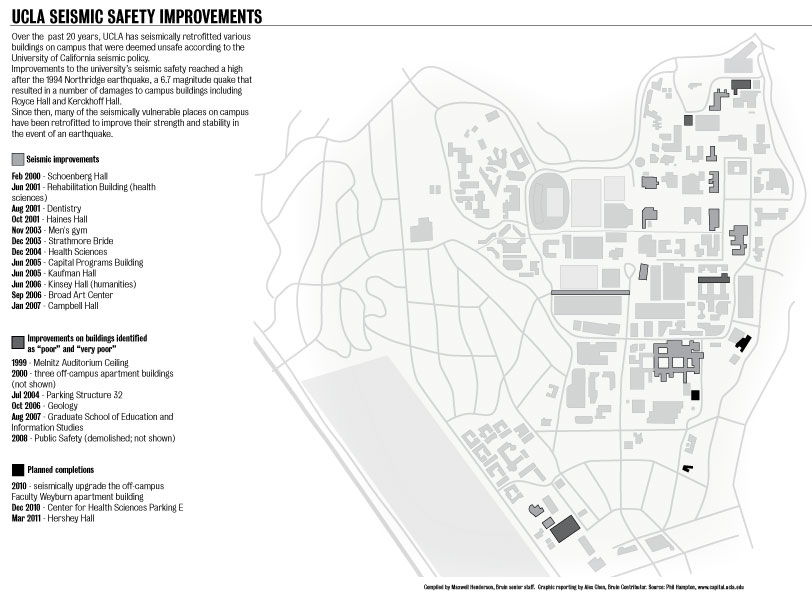

After the 1994 Northridge quake, some university buildings suffered quite a bit of damage, as ceilings and bits of towers broke off from Royce Hall.

But the quake did lead to new efforts to retrofit the campus, and Davis said the seismic safety of Kerckhoff Hall was improved through base isolation.

By placing the building off of the concrete and into rubber, the retrofit ensures that the building will not move as much because of its more flexible foundation, Davis said.

Many of the more seismically vulnerable buildings on campus were retrofitted after the quake to ensure their strength, he said.

Regardless, scientists agreed on the necessity of being ready for whenever the “Big One” hits.

“We’ve become a world leader (for the Great Shakeout Drill),” Davis said. “The most important thing to do is to prepare.”

With reports from Sarah Khan, Bruin contributor.