While UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television may be the first place you would look for connections to Hollywood, you might want to start looking a little further south. Or at the very least, look beyond the walls of Melnitz Hall.

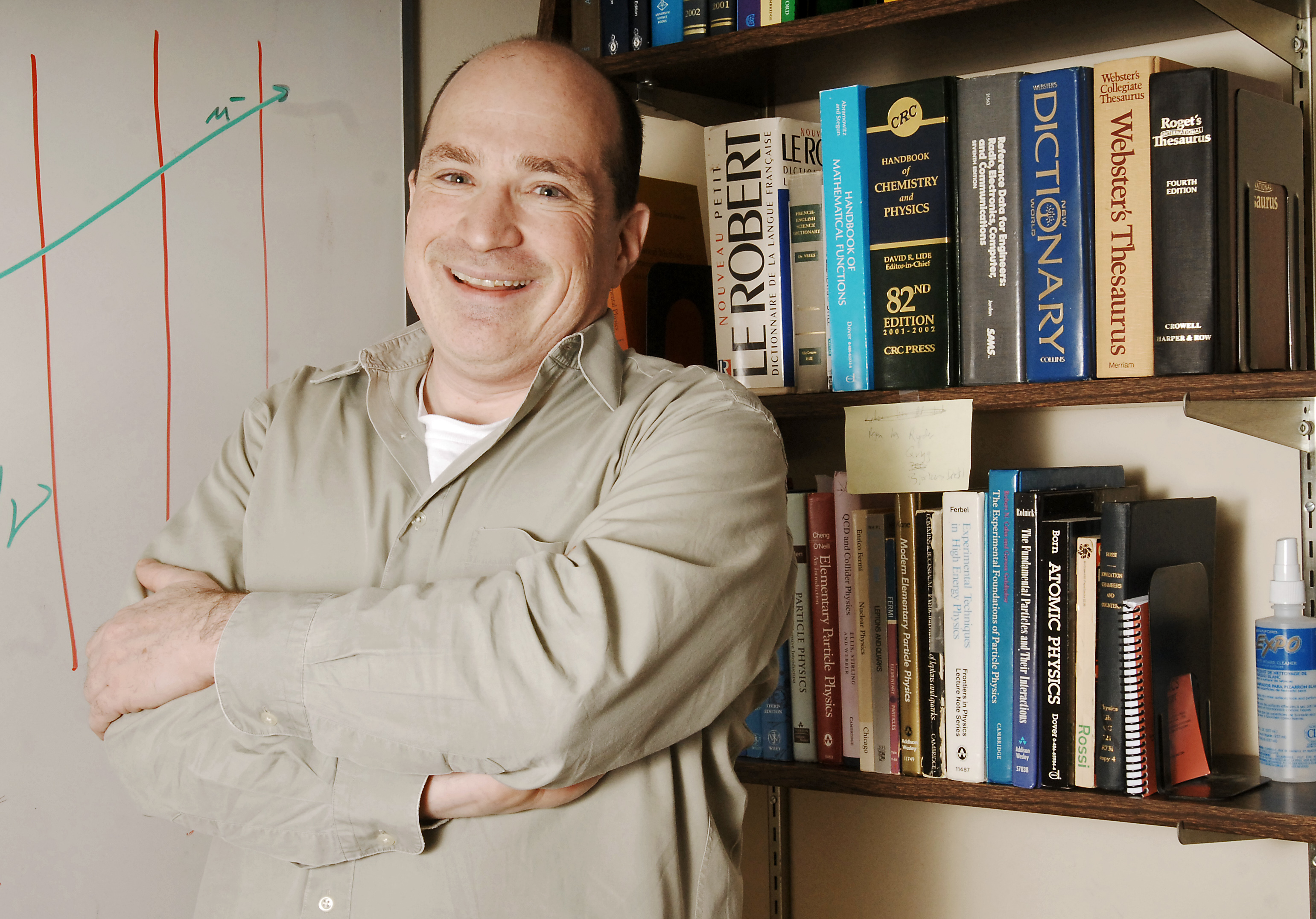

Thanks to UCLA’s proximity to the film and television industries and its prestigious academic reputation, professors from different fields are tapped by film and television production staff for their unique expertise. And while it may seem unusual for a professor to moonlight in Hollywood, David Saltzberg, physics professor and science consultant for the CBS sitcom “The Big Bang Theory,” considers it an extension of his duty as a teacher and researcher.

“I joke about (consulting) being my day job, but part of our job is to explain to the outside world what we’re doing ““ community outreach,” Saltzberg said.

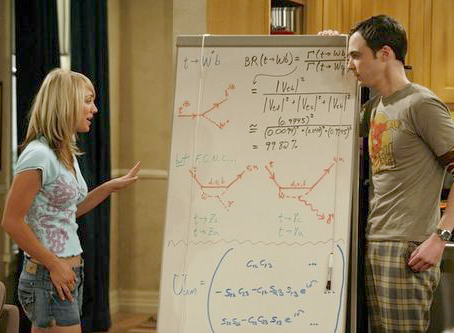

From including current topics in theoretical physics to the show’s dialogue, double checking for accurate scientific information and operating a side blog, “The Big Blog Theory,” meant to expound on information mentioned in the show, Saltzberg has merged his work in physics with the popular television show.

However, the process of going from professor to Hollywood consultant is no easy task. According to Jennifer Ouellette, the director of the Science & Entertainment Exchange, which works to connect film and television production staff with experts from various campuses, Saltzberg’s experience is not the norm. Consulting can range from a 10-minute phone call, to a meeting, to the rare recurring gig and, in many cases, professors are contacted based on Google searches, making the entire process a little haphazard.

“No one in Hollywood has a scientific background,” Ouellette said. “You need to know where to look, you have to know what kind of expertise you need, but instead they just start calling around.”

Through Ouellette’s office, which is located on the UCLA campus, the Science & Entertainment Exchange hopes to facilitate the natural relationship that has developed between Hollywood and UCLA academics in order to provide accurate science in the entertainment industry.

“I think it’s a good thing for Hollywood to know who scientists are and what they do, and it’s also very good for the scientists to see how Hollywood works because they have all these images of what Hollywood is,” Ouellette said. “There’s a reason that we have exchange in our title because this is a sort of cultural exchange.”

Saltzberg said that his experience working on the set of “The Big Bang Theory” has made him much more aware of what it takes to make an a television show. From the number of people involved to the attention spent on set design and costumes, he said the experience has really changed the way he views television.

“Here we are living in Los Angeles, and if you’re a physicist or a physics grad student, traditionally you don’t really have any connection to that,” Saltzberg said.

UCLA Egyptologist and assistant professor in the Near Eastern Languages and Cultures Department Kara Cooney has had her share of frustration with the portrayal of Egyptian culture in film and television, but she also said that it’s a part of Hollywood, whether it’s choosing to include a fifth, not to mention erroneous, canopic jar to a scene in “The Mummy” or turning the scarab beetle into a frightening, flesh-eating creature.

“I’ll tell people that the scarabs are representative of the sun and they’ll ask, “˜They don’t eat your skin?'” Cooney said.

While Cooney’s work on “Lost” as a consultant on its use of hieroglyphics and her own Discovery Channel special “Out of Egypt” hasn’t caused her problems, she points out the issue faced by some professors who choose to engage in consulting: whether or not the information they give will be used at all. In some cases, apparent misinformation has the potential to cause problems within the academic world.

“There’s a misunderstanding that consulting works like the academic world where you sit with an editor, have complete control, etc.,” Cooney said, “The advice could be taken or not taken, so it might not have been the consultant’s fault.”

For Saltzberg, the problem of having his notes ignored hasn’t been an issue, but his choice of information to include has facilitated conversations about different topics in physics, from comments on his science blog challenging him to do further research, to conversations with colleagues and grad students, to the creation of a fictitious Antarctic experiment that’s beginning to sound less and less absurd.

“We came up with this magnetic monopoles in the Arctic idea as kind of a joke, but now I’m starting to think it isn’t such a crazy idea,” Saltzberg said. “So it will be quite funny if it turns out to be a real experiment.”

According to Ouellette, the cultural exchange that comes from science in Hollywood is important for both sides. While Hollywood has a harder time getting away with incorrect science in today’s Internet world of Google searches and entertainment blogs, innovation in science can find its start on the big and small screens.

“Just because something isn’t possible now, doesn’t mean it won’t be possible later. Today the AWARE study is based on the movie “˜Flatliners’ from 1990,” Ouellette said, in reference to the study that concerns consciousness and the human mind during clinical death. “In that sense, I think film and television can inspire science.”