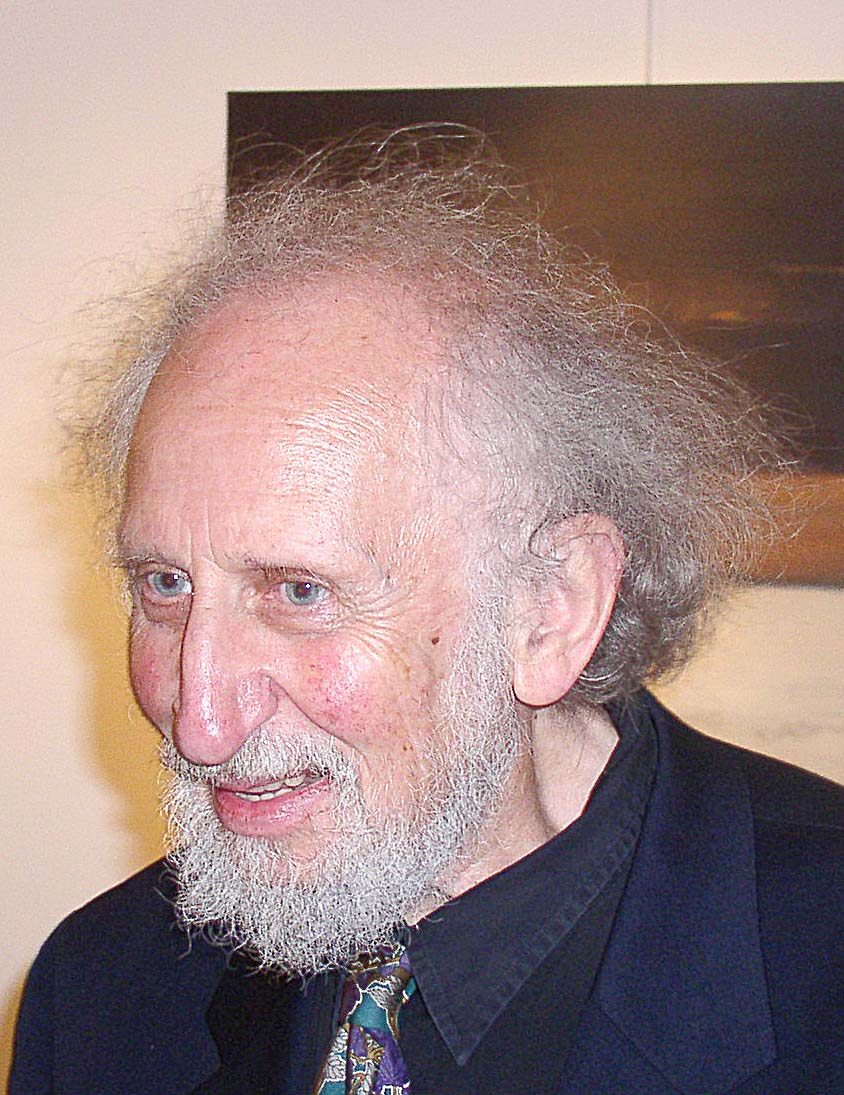

Eli Sercarz, UCLA professor emeritus of microbiology and molecular genetics and renowned immunologist, died Nov. 3 of renal cell cancer at his home in Topanga. He was 75.

Sercarz was known for his research in immunology, especially his discovery of cryptic determinants, which relates to the immune system’s ability to respond to infectious diseases.

“It’s a very difficult philosophical concept,” said Carrie Miceli, professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics, referencing the concept’s idea of self. “But he was part poet and part scientist.”

She added that Sercarz was a bohemian thinker who was drawn to intellectually difficult questions.

With this and other discoveries, Sercarz helped to transform the field of immunology, creating a reputation that preceded him.

“I knew of him before I came to UCLA,” said Sherie Morrison, professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics. “He was a very unique and original thinker … who permeated research and teaching.”

Sercarz was recognized for his efforts with a number of awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Federation of Clinical Immunology Societies and the Nachman International Prize for research in rheumatology.

However, beyond his academic accomplishments, Sercarz was known for his dedicated mentorship of his students.

“He was a devoted teacher of undergraduates,” Morrison said. “He brought humor into the classroom and he felt it was important that he did.”

Miceli echoed these comments, mentioning how Sercarz incorporated his love of food with his lectures to help students understand the material.

Morrison said he also mentored the graduate students and postdoctoral fellows with whom he worked in his research laboratory.

Thus, it was not uncommon for Sercarz to keep in touch with these students, often entertaining them in his home and helping them to find jobs and positions.

“He really treated students like extended family,” Morrison said.

As a result of his dedication, Sercarz was awarded the American Association of Immunologists Excellence in Mentoring Award in 2007, which recognizes exceptional advisers.

But to his colleagues, Sercarz was known as a considerate man who loved to socialize.

Miceli spoke of his willingness to organize speakers at seminars and to host gatherings at his home.

“He was a tremendously generous man,” she said. “He was hugely creative and hugely impactive on a personal level.”

She mentioned Sercarz’s 75th birthday tribute, during which many of his co-workers and mentors came to honor him.

“He wanted people to dance at his birthday party when he was already ill,” Miceli said. “He was a loving person who loved life.”

Sercarz was born in New York on February 14, 1934 to Morris Sercarz and Aida Liberson.

As a teenager, Sercarz lived with his mother in Tecate, Mexico, for a year. He then persuaded her to move back to New York while he finished high school, riding his motor-scooter each day to Mountain Empire Union High School in San Diego County, located across the Mexican border.

After graduation, he attended San Diego State University, where he received his degree in chemistry and later moved to Harvard University for graduate studies, eventually earning a doctorate in immunology. He also held postdoctoral fellowships at both Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology through 1962.

Sercarz came to UCLA in 1963 as an assistant professor of immunology.

He eventually attained the status of “professor above scale,” which is a distinction reserved for professors who have made significant contributions to their fields. He worked at UCLA for 34 years and upon retirement, received the title of professor emeritus.

But in spite of his work schedule, Sercarz always made time for pleasure.

“He was a hardworking man, … but he tried not to impose work on his household,” said his wife, Rabyn Blake.

As a result, the couple attended concerts, movies and ate at restaurants to indulge Sercarz’s love of food.

“He was a real foodie,” she said, laughing.

She added that her husband was a connoisseur of cheeses, sometimes bringing samples home from trips in his suitcase.

“He was so full of life,” said his wife, Rabyn Blake. “He did not waste a minute of his life and was never bored for more than two seconds.”

Sercarz is survived by his wife, Rabyn, and three children.

A private celebration of Sercarz’s life will be held on Nov. 29.

I was fortunate to have him as my professor when I went to ucla. I will always remember him