To Susan Smalley, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, the mind is like a seesaw.

On the right-hand side sits the practical mind-set: the doing, thinking and logical part.

On the left-hand side sits the intuitive mind-set: the “being,” the emotional and creative outlook.

But the human mind is no child’s play; its proper functionality is crucial to maintaining mental and physical health.

According to Smalley, when one side dominates the other, the mind ““ as the metaphorical teeter-totter ““ ceases to function properly.

So with the influx of information and high demands given to over-achieving university students, the individual’s logical mind-set often trumps the creative one. It is a result of the imbalance of the psyche, as well as the contribution of an individual’s genetic makeup and past stressful experiences, that excessive stress becomes an issue.

“Like a lot of things, having a moderate level of some stress is going to help you. When it’s too much is when we see it affecting a person’s choices,” said Ancy Cherian, staff clinical psychologist for UCLA’s Counseling and Psychological Services department.

“When they feel like it is influencing their behavior, we start to see shifts in their thinking, see them doubting themselves, doubting their ability.”

That change of behavior or mood is an outward expression of the body’s physiological body’s response to stress.

Three major pathways are activated during the body’s stress response, said Dr. Michael Irwin, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of UCLA’s Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology.

The sympathetic branch of the body’s autonomic nervous system ““ commonly known as the fight-or-flight response ““ increases blood pressure and heart rate to allow for increased blood flow into the body’s vital organs.

According to Irwin, the succeeding active response uses cortisol, a hormone that allows the body to use up glucose for sustained energy during the period of stress.

The inflammatory response, the third response, provides proteins to immunity cells in order to strengthen the immune system and prepare the body for a physically harmful scenario.

While a stressor initiates such involuntary physiological responses, there is no standard measure of excess in regards to stress. Instead, stress level accords to an individual’s circumstances, Irwin added.

“If (people) have experienced more severe traumas, they are more likely to have exaggerated responses when they experience similar events when they are adults,” Irwin said.

Exposure to previous stressors, the severity of the event at hand and the individual’s genetic makeup are determinants of the magnitude of the biological response to stress, added Irwin.

“Previous experience has two effects: In one instance, we learn how to adapt. … However, in other instances for other people, they may fail to adapt because they didn’t understand or couldn’t master the stress to begin with,” Irwin said.

Such unmodifiable factors related to stress can be offset by voluntary controls such as maintaining consistent sleep patterns and healthy eating practices. These habits fortify the body with the nutrients and energy it needs to regulate its vital systems and their management of stress.

Additionally, daily exercise, healthy relationships and meditative breathing create stability for an individual. Mindful thinking, encouraged by meditative breathing, activates the parasympathetic response ““ the marked decrease in heart rate ““ to counter the sympathetic response’s elevation of heart rate.

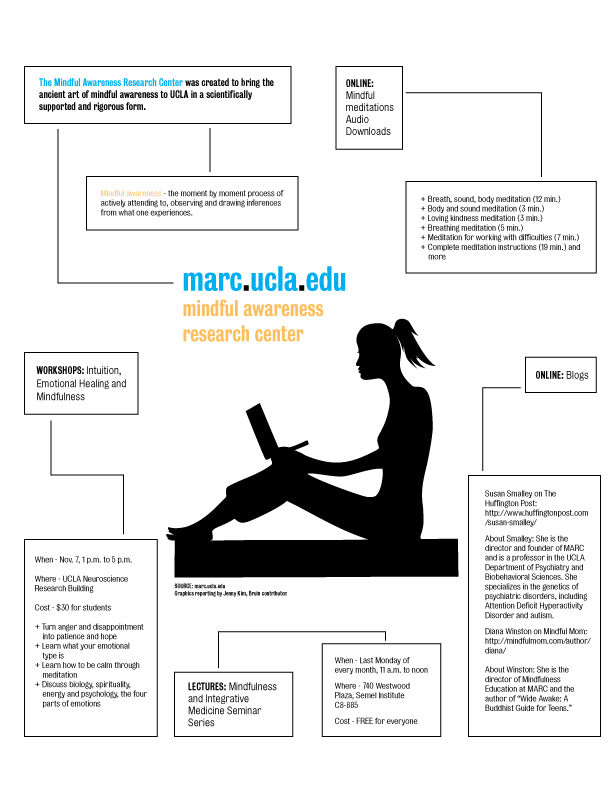

“Adding mindfulness allows you to explore your mind, calm your mind, investigate the roots of your emotions, your anger. “¦ Part of learning about mindfulness is how to integrate these things into your day-to-day life,” Smalley said.

As part of creating a daily ritual of meditative breathing, Smalley said calm breathing can be incorporated into regular activities, like the time spent walking to class.

Another part of mindfulness is responding proactively to the source of stress. Particularly among college students, procrastination can worsen stress levels if used as a method to avoid or delay the onset of the stressor.

“When we procrastinate, that means during those times we’re up against a deadline, we might be foregoing other needs: social needs, households needs. … All things that keep us balanced,” Cherian said.

That maintenance of balance harkens back to Smalley’s analogy of the seesaw.

With so many stressors bombarding the human body and psyche, maintaining balance becomes the most fundamental element of stress relief and prevention.

“(Mindfulness) isn’t a natural way of living in the 21st century. Running around thinking about tomorrow, we don’t allow ourselves a possibility to be present and exploring,” Smalley said.

“True wellbeing arises when you integrate reason and processes that can’t be explained by science or rational mind.”