The best moment of Sydney Leroux’s life remains clear, crisp and strikingly simple in the soccer player’s head.

“Two girls ““ crying,” she succinctly synopsized.

The other “girl,” Sydney’s mother, Sandi, choked up over the phone when she thought about the call she got from her daughter.

“We cried, oh my God,” Sandi said. “It was all worth it when she called home that night.”

Sydney called her mother from Chile shortly after she won the Under-20 World Cup and the Golden Boot top scorer award to go with it in December.

And it was all worth it because Sydney and her mother gave up so much for that moment of shared victory.

Sydney gave up a normal childhood, moving six times from the age of 15 to 18, all away from her home and her mother in Canada.

For her part, Sandi gave up her daughter ““ the soccer player whose mom never missed a game, the girl Sandi raised alone.

Sydney lost friends, Sandi lost respect.

But the pair never lost each other.

Leroux has several tattoos scattered across her body. But the one on her lower back might be the most important.

Little hearts swirl around simple stick figures of a mom and her kid holding hands.

The inscription, equally simple, reads, “You believed in me first.”

Determined to leave

Even at 15, Sydney knew she had talent to go along with a big personality that is still evident today.

“She’s determined,” her mother said.

Then after a pause, “She’s stubborn.”

The stubborn side was never more evident than the day the adolescent Sydney decided to offer her mother an ultimatum.

“I kind of started being that little 15-year-old caught off track,” Sydney said. “I told my mom in the summer … “˜If you don’t move me to the States, I’m not going to play anymore, I quit.’ The next day I was on a plane to Arizona, and I didn’t come back home.”

The stubborn teenager’s persistence paid off at least for the moment. Sydney has dual residency in Canada and the United States because her father is a North Carolina native. Sydney was young but old enough to know that the opportunities to play soccer would be much better on the other side of the border.

And so, she went.

“She loves the game of soccer,” Sandi said. “Her goal is to make the national team one day, that’s why she moved down to the States. She was 15. She left home at 15 to do this.”

Perhaps Sydney didn’t realize what leaving would mean for her life trajectory.

She would learn quickly.

The hardest thing

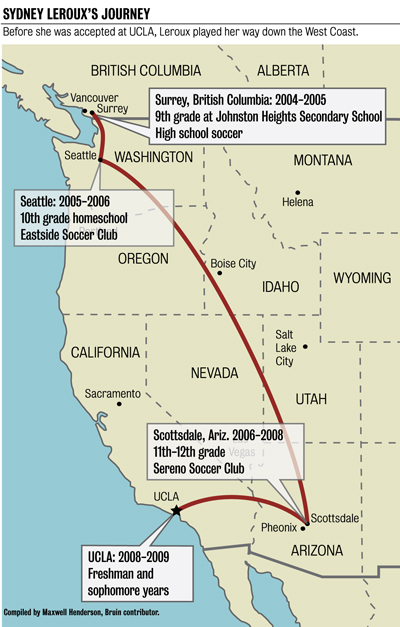

When Sydney first left, the destination was Washington, a place close to home where she could homeschool herself. Utter homesickness brought her back to Vancouver, British Columbia, but soccer drove her back to Arizona for two years before she settled into life at UCLA.

“I can’t even tell you how many places I lived,” Sydney said. “It was really hard. … Probably the hardest thing I ever had to do was kind of just pick up my life and try to move it all to Arizona. I went from having all of my friends to trying to start a new life.”

Sydney found herself without a real home base for much of her stay in Scottsdale, Ariz. As she had done for the last few years, she was forced to bounce from house to house and try to keep up with schoolwork even though she traveled extensively with the U-20 national team.

But perhaps it was Sandi who was hurt most by her daughter’s tough times. The mother who worked graveyard shifts so she could watch her daughter play said that many people looked down on her as a parent for letting Sydney go.

“The hardest moment was the way she got treated,” Sandi said. “She left Canada knowing everybody knew her, and she had a lot of friends. She moved into the Scottsdale area, a rich area, and people were snotty. She’d phone home and say, “˜Mom, I have no friends.’ And that part was really hard on me. It was horrible. That part probably was the hardest because I wasn’t there to give her a hug.”

And Sydney probably could have used one. To Sydney, finding friends was a secondary concern.

She missed her mom.

Even as late as age 14, Sydney admits that she would call her mother at 2 a.m. when sleeping over at a friend’s house, struck with homesickness. Sandi never failed to get in the car and pick her daughter up.

That made the teenager’s choice to leave home even more perplexing to those who knew her. And it certainly didn’t make life on the road easy.

“Being away from (my mom) was definitely harder than not having friends,” Sydney said. “I didn’t have friends for the first year, which was weird for me because I’m a pretty outgoing person, and I like meeting new people. But when I got to Arizona that part of me just wasn’t there. I think because I missed my mom so much, it completely changed me. … I didn’t want to do anything. I can’t count on my hands how many times I wanted to go home. I missed my mom, I missed my friends, I missed having friends.”

A Wall of support

Sydney not only didn’t have a house to call her own, she also had to continually work out logistics of small things like getting to and from soccer practice.

She solved that relatively minor problem by turning to Dana Wall, a friend who would later be her teammate at UCLA. Wall, who is also a Daily Bruin photographer, played for the same club team as Sydney, but because Wall was a year older, they played on different teams. Luckily, practice would often start at the same time for the eventual Bruins, and the teams would even practice together on occasion.

They didn’t even go to the same high school, but Sydney’s outgoing personality immediately struck a chord with Wall.

“She was very open from the beginning,” Wall said. “I would give her rides home from practice, and she would tell me stuff about home and how she ended up here. And she would ask me questions, too. It wasn’t all about herself. It was really quick that we clicked.”

And while the soon-to-be teammates were bonding in soccer vans, Sydney found herself needing to move yet again. She was staying in a teammate’s home, which housed multiple kids, and she didn’t have much in common with the family.

Desperate to get out, Sydney looked to Wall for a slightly larger favor: a place to live.

“Honestly, I didn’t know it was going to be a year … but it was just something where you just couldn’t say no,” Wall said. “She was such a good member of her team, and she had been through so much.”

Wall said that Sydney fit into her family seamlessly and did a great job making herself available to help whenever possible.

The two talked all the time, Wall often serving as a release valve when a twinge of homesickness would strike Sydney.

But they had fun together, too. In fact, what drew Wall to Sydney was a funky facial expression caught on camera.

“I have this certain facial expression that I make,” Wall said. “It’s like a funny face. I was looking at a picture of (Sydney) on her school binder, and she was making the pretty much exact same face. And I was like “˜Oh my God, you make the same face, too.’ It was just funny because you could just tell that we both have very similar personalities. We both are just really goofy and funky and stuff. We first started bonding over making jokes and being stupid. She has a hilarious personality when she is not being super intense.”

Yet for Sydney, there was still something missing. Even though she said that she became really good friends with Wall, Arizona still wasn’t home.

“I would just say I got used to it,” Sydney said. “I did find my friends eventually. I wouldn’t say it got easier, I think I just found a way to deal with it better. From the day I left home, it was always hard.”

Soccer was still Sydney’s release from a stressful world ““ still the only place she could really laugh and have fun. As she neared the end of high school, however, even soccer got serious. She narrowly chose UCLA over Santa Clara after making an official visit to the campus where she hung out with Wall, now a Bruin away at school. And the 2008 Under-20 World Cup was fast approaching.

Getting her chance

Upon arriving at UCLA and leaving the stresses of Arizona, new problems followed Sydney to Westwood and then across the globe.

For an entire year, Sydney practiced with the Under-20 team in preparation for the World Cup. As she did this, she played in the first half of UCLA’s season, a season that would see the Bruins advance to their sixth-straight College Cup, only to be topped by eventual champion North Carolina, 1-0.

Just before the postseason began, Sydney left UCLA for Chile to join the national team for the Cup. In doing so, she left a team on which she started, for a team on which she would warm the bench. She traded a potential national championship for a potential World Cup and risked losing playing time.

But just as she had done at age 15, Sydney was willing to take the risk if it meant helping fulfill her soccer dreams.

“Do I think I could have made a difference (against North Carolina)? I don’t know because I wasn’t there,” Sydney said. “Do I think I was capable of making a difference? I do.”

She thought the same way about her role on the national team. Her status as a bench warmer frustrated her to no end.

“For me that is one of the hardest things,” Sydney said. “I had given everything away. Yes, I’m going, yes, I’m wearing this jersey, but it’s not filled with sweat, it doesn’t have blood on it, there are no grass stains. I’m clean. And that wasn’t enough for me. I can’t tell you how many times I just wanted to scream, “˜Just give me a chance!'”

Then, during halftime of the United States’ first game against France, she got her chance when her coach told her to warm up.

“I was just fired up,” she said. “I was excited, I was mad, I was angry, I wanted to prove people wrong. I knew that even my team didn’t think I was a starter.”

Playing the quintessential role of a substitute seizing the moment, Sydney assisted the first goal of the match and then scored two of her own in the United States’ 3-0 win over France.

From that game forward, the former benchwarmer started every game and played nearly every minute. But the team’s success presented yet another problem: Would Sandi spend thousands of dollars to fly to South America to watch her daughter play?

After long talks, the mother-daughter tandem decided there was too much uncertainty to take that risk. So for the United States’ championship match against North Korea, Sandi found herself driving across the border to a Washington restaurant where the game was being broadcast.

Although she wasn’t physically present at her daughter’s game as she had been so many times before, Sandi’s experience watching her daughter score was exciting and joyful in its own way.

“I was crying and laughing, and I was all by myself,” she said. “And then the final game, everyone came in, they thought it was NFL Sunday football and they were all mad, and I would say, “˜That’s my daughter’ and suddenly everyone was watching the soccer game.”

When the game was over, Sandi got the phone call she will remember for the rest of her life.

“I went back to the hotel, the first thing I did was I went on Skype, and I called my mom’s phone,” Sydney said. “And she was crying and I was crying, and everything was just so emotional for both of us. That was probably one of the best moments of my life. She just said “˜I knew you could do it.’ I couldn’t even talk to her. I was just balling. That conversation was just crazy.”

Not done yet

Somehow, the young woman who teammates call “Syd” isn’t anywhere close to being done yet.

The starting forward said she learned an inordinate amount from her World Cup experience ““ particularly how tough it is to sit on the bench.

Her coach Jillian Ellis, the Olympic national team’s assistant coach, said that the sophomore is maturing, which aids her “fantastic talent.”

The stat sheets reflect Sydney’s growth ““ her six goals lead the team this season.

But Sydney remains unsatisfied. She wants a national championship for UCLA badly, and she desperately desires a chance to play on the U.S. Olympic squad alongside her teammate Lauren Cheney.

But for the moment at least, she has what is most important to her.

Last weekend, her mother Sandi did what she had always done before her daughter moved away. Wearing a jersey with the letters “Leroux” stitched to the back, Sandi cheered as she watched her teenager-turned-adult sprint across the Drake Stadium grass.

If the mother and daughter exchanged a hug after the game and shed a tear during their embrace, the scene might resemble a lesser version of what could have been in Chile.

Sydney’s journey from her 15-year-old self may have been long, and it may not be over.

But it’s safe to say that it was all worth it.