The first patient is always the hardest.

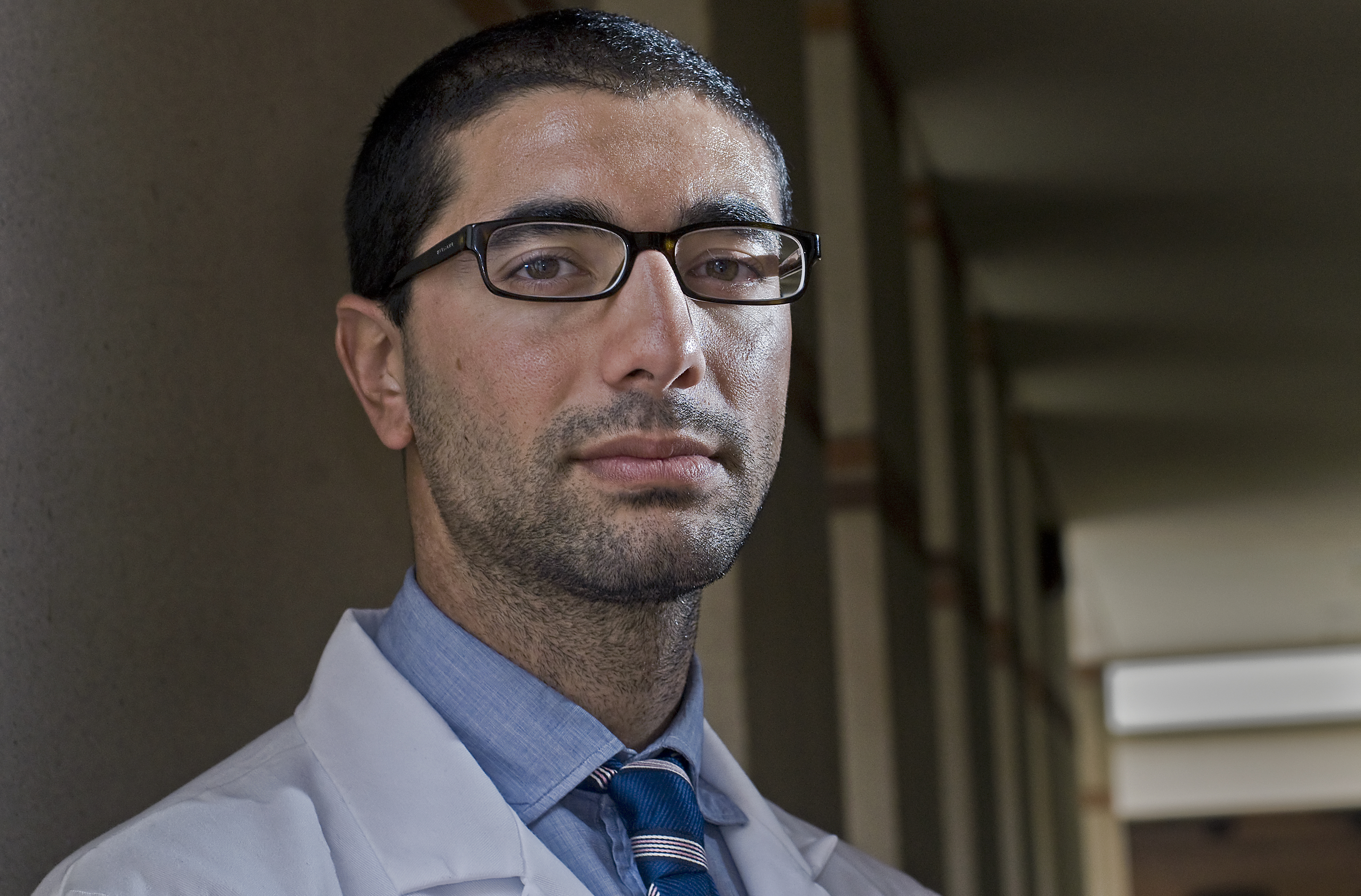

“It gives you a sensation that’s not quite shocking, but the reality of it hits you hard,” Omar Kattan said. “We were apprehensive, and really all we did the first day was open up and reveal the body, closed it and went back. But just that little act had a big impact on me.”

It was a rite of passage for Kattan and thousands other first-year medical students: their first gross anatomy dissection. For the next six months, students would know cadavers in both intimate detail and complete obscurity; they would probe nerves and muscle without learning the owners’ names, touching hearts and picking brains in only the most literal sense.

For the body, though, this was the end. Its journey to the dissection table was perhaps more remarkable still.

To elite medical schools, many things have a price. Money buys equipment, prestige attracts faculty, and collective ingenuity brings good publicity.

It is especially striking, then, that the training of every physician in the world requires an asset with no asking price at all: the cadaver. Donors sign the consent form expecting neither fame nor compensation, moved only by a quiet trust in scientific progress.

As director of the UCLA Donated Body Program, Dean Fisher stewards this vital trust, He shepherds the roughly 140 annual gifts from expiry to the examination table.

But this is no easy task. Along the way, Fisher juggles roles as embalmer, grief counselor and occasionally an executor of last wishes.

“I have a sympathy for each family ““ that we’re treating their loved ones as if they were our own mothers and fathers,” he said. “If you treat (the families) well, they will treat you with the same kindness. You meet so many neat people along the way, find them in such a difficult and troubling part of their lives, and you help them get through that.”

The program offers to retrieve all donations within 75 miles of UCLA. Once on campus, a battery of tests scan for HIV and hepatitis before the body is embalmed.

At that stage, a needle threads into a small incision in the hip, replacing the blood with a mixture of preservatives ““ formalin, ethyl alcohol, phenol and propylene glycol. Finally, the cadaver cures under a muslin sheet in 40 degrees Fahrenheit, awaiting study.

“The science of preserving the body is always a little challenging because it’s a little different from how mortuaries do it,” Fisher said. “They are more concerned with appearance, so they use more dyes to make the body look nice.

“But we have to make sure every square inch of that body is preserved.

Those students are going back three or four months later to study them

on the dissection table.”

Cadavers pose an additional twist. Not only teaching specimens, they are also the remains of fathers and mothers, friends and loved ones.

Accordingly, Fisher’s responsibility spans both the scientific and sacred. During his tenure at the Mayo Clinic, one donor had wished for his ashes to be strewn across the horseshoe pits where he worked at IBM.

“The family asked me if I’d just take his ashes and put him on Horseshoe Pit No. 2,” Fisher said. “So I went out there right as the gates opened at sunrise one morning, watched the security guard drive away, and I stopped and fulfilled that wish. The family couldn’t be more happy. It was where he loved spending his extra time.”

As far as donors go, Lupe Mageno was a classic case. In life, she cared for stray animals, sometimes sleeping outside with them to help stave off their loneliness. She was eager to sign the consent forms authorizing her final gift.

“Most of the family didn’t (like her decision). They wanted the coffin and all that stuff,” her daughter Rosalie Ortega said. “But we said no, mother had written down what she wanted to do, and she made that clear to us: “˜I decided this and that’s the way it’s going to be. There’s no use in wasting me.'”

A recent memorial service at UCLA brought first-year medical students and donor families ““ including Ortega, Kattan and Fisher ““ together to honor these contributions.

To families, it provided a final degree of closure. But for the students, it revived emotions they had learned to sequester so tidily before each dissection.

“Personally, I just took a moment to remember the person before starting each time, no matter how frustrated I was with the material,” Kattan said. “(I took) moments before and after, actually, to remember that this was a human, a person just like me.

“Because to be honest, I still can’t fully register what they’ve done for us ““ probably not until I’m 10 or 20 years down the line and really remembering.”

The service featured poetry and live musical performances by the first-year students, culminating in a solemn memorial for all donors. When the students read her mother’s name, Ortega sat clutching a camcorder as tears coursed down her cheeks.

“I was there when she passed, and they came with a royal purple robe to put over her,” Ortega said. “To me, it was all very dignified, and they treated her like a queen. … She was just a queen bee. When the young man put it on and finally took her away, we felt a real peace and comfort.”

Last January, UCLA brought Fisher from Mayo to reinstate a program that had been closed for 18 months due to corruption scandals that plagued its last director. Fisher’s mellowing attitude, though, belies the gravity of his responsibilities, as he chooses to focus on the fruits of his labor.

“When I first started, I watched college graduates grow into medical students and go through residency, and now they are my doctors and they’re treating me,” he said. “A pediatrician takes care of my children now ““ one I helped train.

“This is what gives me satisfaction ““ to say that I had a little part in their education, to take these young adults and turn them into some of the best doctors in the world.”

As for Kattan, his ambitions lie in a specialty where UCLA has the most active program in the world: liver transplant surgery. This field will mean years of extra training and residency, though an unlikely mentor has already laid the groundwork.

“Doctors like to say that being a physician is about being a teacher,” Kattan said. “But I really believe that we learn from our patients, as well. And I think this first patient gave me probably the biggest lesson I’ll have in my career.”