A week after the swine flu’s rampant invasion of media coverage and public health statements, the public’s adverse reaction toward the virus, now called influenza A (H1N1), seems to have spread faster than the virus itself.

Originally referred to as the “swine flu” because laboratory testing determined its genetic similarity to viruses normally occurring among pigs in North America, recent research has determined that the virus contains a different molecular structure from other normal virus strains within pigs.

“Pigs are so unique because they can get sick with human flu, pig flu, bird flu; pigs are a mixing tank for all the viruses, so you can see reassortment very commonly in them,” said Dr. Zachary Rubin, epidemiologist at Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center and Orthopaedic Hospital.

In a “quadruple reassortant” virus such as this, the segmented genome can contain bits of reassorted DNA as a result of two strains coming into close contact with each other.

“This new flu virus comes from the genes of two swine, one human and one avian influenza virus. It probably originated in a pig infected simultaneously with two or more flu viruses,” said Dr. Larry Baraff, chief of pediatric emergency medicine at Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA.

“This simultaneous infection allowed the viral genes to be reassorted and reassembled into the new flu H1N1 virus. Though it is initially isolated in humans, it’s more likely the initial infection was in swine,” he said.

Although the Center for Disease Control and Prevention is uncertain of the virus’s exact origin and how easily it is spread between humans, they are currently studying the medical histories of infected persons to determine what types of populations would be at greater risk for infection.

While individuals over 65 years of age, children under 5 years of age, pregnant women and individuals with chronic illnesses are most at risk for contracting the seasonal flu virus, this particular strain could affect a wider range of the population.

“With a new and genetically different flu virus, children and young adults can be severely affected because of lack of antibody from prior infections,” Baraff said.

As of now, the threat of the swine flu as a contagion has declined in relation to the comparative threat of the seasonal influenza, which takes its course beginning in the winter months ““ from November to January or February ““ and usually fades around April.

It is because of the flu’s high degree of contagiousness that H1N1 and the seasonal flu can pose severe potential threats to the health of the general population.

“People forget about the seasonal flu and how serious it is. Between (30,000) and 90,000 people die a year in the U.S. alone, and it’s the leading cause of death in U.S.,” Rubin said.

“Pandemics get play, but the seasonal flu we take very seriously in the hospitals because it causes so many deaths. We always emphasize pandemics when they’re around, but this is also an opportunity to publicize the seasonal flu.”

Despite the population’s increased vulnerability to the H1N1 strain and the CDC’s uncertainty of the virus’s exact origins, animal-based strains do follow a general trend of contamination and transmission.

“The way viruses are transmitted to humans, they have to start in water fowl, like ducks, who will carry the virus and shed it in their stool, which then will spread to waterways … where pigs get it, and which can then spread to humans,” Rubin said.

Although H1N1 most likely originated in Mexico, common flu strains usually originate in Asia, according to Rubin. Around six months before flu season generally begins, a flu strain will circulate around Asia.

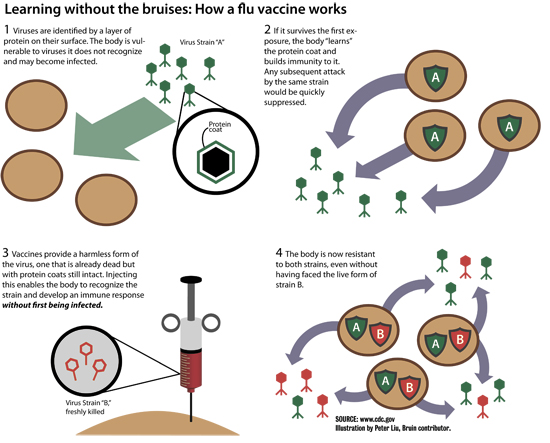

By manipulating certain proteins within the circulating virus strain, researchers will then predict which virus they presume to be the most predominant seasonal strain and will send their results to public health labs, including the World Health Organization and the CDC. The results will then go on to vaccine producers in order to distribute the vaccines to the public.

“Every year is different from predominant strains (from before). Scientists essentially make an educated guess about what’s going to be the predicted strain that year,” Rubin said.

Since the extent of its spread is based on retrospective analysis, scientists analyze past influenza pandemics to provide a helpful comparison between past and present strains.

Though this strain is relatively unknown in regard to its genetic and chemical composition, it does not exhibit similar characteristics to that of the 1976 scare, which never materialized into an epidemic, or to the 1917-1918 influenza pandemic, in which more than 50 million people died worldwide.

“The 1918 pandemic was a disaster. It was very deadly, very widespread,” said Dr. Peter Katona, associate clinical professor of infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “It looks like what’s happening in the A (H1N1) strain is consistent with the genetics that we already know. There is a certain protein it’s missing that was very destructive in the 1918 strain.”

Nevertheless, the ability for the influenza virus to reassort its genes and mutate easily explains its extreme unpredictability.

“We don’t know the likelihood, but there is certainly potential for A (H1N1) to come back, because these kinds of genetic variants have done that in the past,” Katona said.

The virus’s full effects cannot fully be determined until months from now, since the warming spring temperatures of the Northern Hemisphere could have diminished the efficacy of the virus’s transmission between humans.

“The spread will decline in the Northern Hemisphere, where it’s warmer here. We know from animal research that increasing temperatures and lower humidity … negatively affects virus transmission,” Rubin said.

The coming winter months and general unpredictability of the flu virus explains the necessity for expediency in the research and public distribution of a vaccine geared specifically toward building immunity to the strain.

According to Baraff, each year an expert committee member from the Food and Drug Administration decides which three strains of the flu virus will be present in the following season’s vaccine.

“It has not yet been determined if this particular strain A (H1N1) will be in the vaccine for 2009-2010. They’re trying to make that decision now.

“They like to use a virus that has been widely present in the last year, so A (H1N1) would be a good candidate,” Baraff said.